Classification

Worldwide, there are approximately 800 species of the order Anguilliformes, the eels, varying in size from 2 inches (5 centimetres) to 13 feet (4 metres).

Conger (top) and yellow eel

Life history

It was not until the last years of the 19th century that zoologists observed the transformation of eel larvae, or leptocephali, (previously thought to be a separate species), into juvenile eels. This led the Danish professor Johannes Schmidt to carry out many expeditions through the Mediterranean and Atlantic, observing the occurrence, distribution and size of leptocephali. Schmidt's research, over nearly 20 years, eventually led to the conclusion that spawning takes place in the Sargasso Sea, to the east of Bermuda. Despite this apparent breakthrough, spawning has never been observed, nor have adult fish that are ready to spawn.

After hatching, the eel leptocephali, transparent leaf-like creatures, begin their eastward journey across the Atlantic, carried by the Gulf Stream. Eventually, after 1 - 3 years, and at a length of 75 - 90mm, they reach the coasts of Europe, and transform into glass eels, still transparent, but much more recognisably eels. The arrival of glass eels usually begins around February, reaches a peak in April, and in some exceptional years may continue until June.

Glass eels & elvers ascending an eel pass; © Environment Agency, 2013.

The glass eels tend to accumulate at the point in the estuary or river where STST no longer results in an overall upstream movement, and so above the tidally-influenced section of rivers, they begin active migration, swimming upstream and eventually reaching the smallest of watercourses, even crawling out of the water through wet grass and sand to reach unconnected ponds.

While in the glass eel phase, they are particularly vulnerable to fishing (as glass eels are eaten as a delicacy and taken for farming adult eels), predation by other species, impingement in water intakes, and to artificial barriers such as dams and weirs which prevent their access to the headwaters.

From "British Freshwater Fishes", Sir Herbert Maxwell, 1904.

From "British Freshwater Fishes", Sir Herbert Maxwell, 1904.

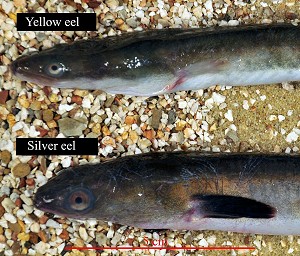

Once settled in fresh water, they complete their transformation into young eels, or elvers, although the word is confusingly also used to describe them in the glass eel phase. Over the next 10 - 15 years, they grow in to adults, known as yellow eels, for their golden-tinged colouration; in this time they reach up to 3 feet (1 metre) in length - exceptionally as much as 5 feet, or 1.5 metres. The female generally grows considerably larger than the male; any eel over about 50cm in length is likely to be a female. Eels kept in captivity have reputedly lived as long as 84 years, if old accounts are to be believed.

Comparison of the heads of a yellow and silver eel

They begin to migrate downstream, again sometimes leaving the water to cross wet grasslands and reach rivers, and ultimately, the sea. Along this journey, their gut begins to atrophy, so during the sea-borne phase of their life they are entirely reliant on their body's reserves of stored energy.

Although many tracking experiments have been carried out, the oceanic stage of their journey, the precise location of their spawning grounds, and their spawning behaviour, remains a mystery.